The two largest forms of out-of-school time (OST) programs are academic and athletic. A vast majority of the academic OST programs go towards closing the gap in underperforming students. Athletic OST programs help work towards the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation that adolescents ages 6-17 years should do 60 minutes or more of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each day (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

The Richmond Cycling Corps has taken the Legacy race team on trips across the state of Virginia, competing both in the NICA and VAHS leagues.

Despite these recommendations, only 26.1% of adolescents are attaining 60 minutes of physical activity as of 2017 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). So nearly three-quarters of all adolescents are not meeting the recommendations of the CDC for the amount of physical activity. These numbers have been fairly stagnant only dropping from 28.7% in 2011. The state numbers for adolescents in Virginia are even lower than the national numbers showing only 23.8% meeting CDC guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

The benefits of out-of-school time programs are also advantageous to parents. The normal workweek of 9-5 leaves many parents in the dilemma of what to do during the 3-5 PM hours where school time typically does not exist. This leaves 7.7 million children alone and unsupervised in the United States (American After 3PM, 2020). Therefore, parents are keenly interested in finding out-of-school time programs for their children. 81% of parents with a child in an afterschool program agree that this helps them work more hours (American After 3PM, 2020).

Cycling is our platform for change. We have fun. We laugh. We teach. We learn. We have a passion for being a positive impact on the kids in the heart of public housing.

However, access to out-of-school time programs are generally dependent on family income. High-income families spend almost seven times more on enrichment activities for their children (McCombs et al., 2017). These enrichment activities help to build social experiences and expose children to adult life. We also see that programs that have been around for longer periods of time tend to charge parent fees, which makes them less likely to be serving underprivileged communities (Earle, 2009).

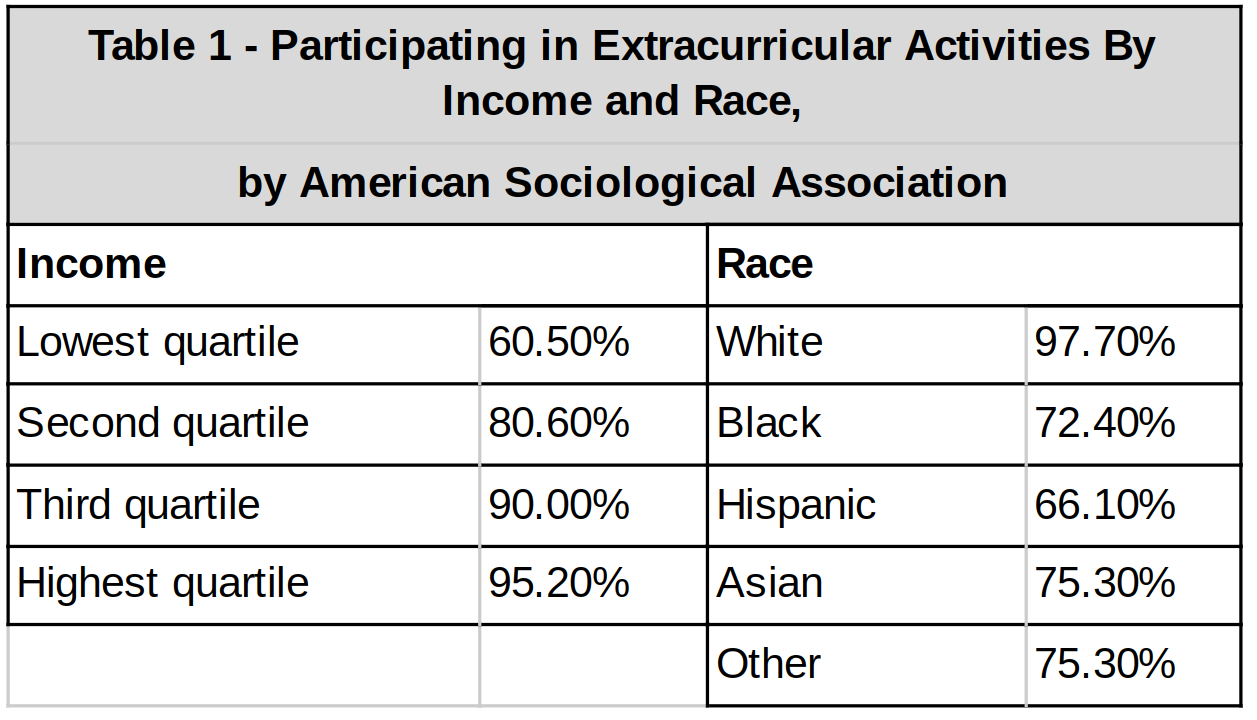

Table 1, shows students from the lowest quartile of families based on income participated in extracurricular activities at a 60% rate (Covay & Carbonaro, 2010). That compares to the next quartile at 80.6% and the top two quartiles showing participation at 90% and 95.2% rates. Sports are the most popular of all the extracurricular studied. When using race to examine participation rates, Whites are the most likely to participate at 88% with Blacks at 72%, Hispanic at 66%, and Asians at 72% (Covay & Carbonaro, 2010).

When it comes to OST programs that involve athletics there remains a gap between affluent kids and kids that are living in poverty. Children from families that have annual incomes of $75,000 or more have an 84% participation rate in youth sports (McCombs et al., 2017). Comparatively, only 59% of children from low-income families participate in sports.

What starts on a bike does not end with a race or a ride. We aim to develop the whole person as we contribute to the lives of young people in Richmond’s East End.

As we see with some social service nonprofits, the line between efficiency and effectiveness gets blurred. As government grants continue to make up a large portion of funding for OST programs, the necessity exists to be efficient, not only in providing the services but in requesting the grants. With efficiency at a premium, effectiveness can be a consequence. With blind efficiency, we are trying to have the best service for the lowest cost. But where does that leave OST programs looking to fill a need for youth in underserved communities. And will new OST programs be able to grow and challenge conventional thinking?